At the age of 18, Austin Osman Spare was being exhibited at the Royal Academy and hailed as an artistic genius. Twenty Years later he was all but forgotten, selling pictures for a pittance in local pubs. Today Spare's artworks command a small fortune, and his writings have spawned a whole generation of occultists. PHIL BAKER profiles the strange career of this extraordinary artist, visionary & magician.

At the age of 18, Austin Osman Spare was being exhibited at the Royal Academy and hailed as an artistic genius. Twenty Years later he was all but forgotten, selling pictures for a pittance in local pubs. Today Spare's artworks command a small fortune, and his writings have spawned a whole generation of occultists. PHIL BAKER profiles the strange career of this extraordinary artist, visionary & magician.

Austin Osman Spare had his career the wrong way round, beginning as a West End celebrity and ending up in an obscure South London basement. By the time he died, in 1956, he had been largely forgotten by the 'straight' art world, but since his death he has become a legendary figure, not just for his remarkable art but for his even more remarkable inner life as a twentieth century sorcerer and magical thinker.

Born in Smithfield in 1886, the son of a policeman, Austin Spare was hailed as a prodigy, genius, and all-round enfant terrible of the Edwardian art world. The youngest exhibitor at the 1904 Royal Academy exhibition, Spare went on to attend the Royal College of Art, where he dropped out without completing the course, and had his first West End show at the Bruton Gallery in 1907. Some critics liked it ("almost unrivalled"; "his management of line has not been equalled since the days of Aubrey Beardsley; his inventive faculty is stupendous and terrifying in its creative flow of impossible horrors"); but others didn't, already seeing Spare's work as abnormal, pathological, and degenerate. George Bernard Shaw is supposed to have said that Spare's medicine was too strong for the normal man. At this stage, controversial as he was, Spare was still "the Darling of Mayfair", but it was not to last. Later he would be selling pictures in South London pubs, and advertising his 'Surrealist Racing Forecast Cards' through a small ad in the Exchange and Mart.

Born in Smithfield in 1886, the son of a policeman, Austin Spare was hailed as a prodigy, genius, and all-round enfant terrible of the Edwardian art world. The youngest exhibitor at the 1904 Royal Academy exhibition, Spare went on to attend the Royal College of Art, where he dropped out without completing the course, and had his first West End show at the Bruton Gallery in 1907. Some critics liked it ("almost unrivalled"; "his management of line has not been equalled since the days of Aubrey Beardsley; his inventive faculty is stupendous and terrifying in its creative flow of impossible horrors"); but others didn't, already seeing Spare's work as abnormal, pathological, and degenerate. George Bernard Shaw is supposed to have said that Spare's medicine was too strong for the normal man. At this stage, controversial as he was, Spare was still "the Darling of Mayfair", but it was not to last. Later he would be selling pictures in South London pubs, and advertising his 'Surrealist Racing Forecast Cards' through a small ad in the Exchange and Mart.

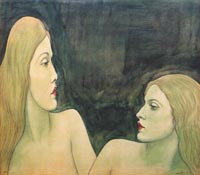

Meanwhile Spare became the editor of Form - A Quarterly of the Arts, and wrote an article promoting automatic drawing in 1916, some years before the surrealists made it famous. He was conscripted into the Royal Army Medical Corps and went on to become an official War Artist, illustrating the medical history of the war. A number of his pictures from this project are in the Imperial War Museum. Back out of uniform, Spare became the co-editor of another quarterly, this time The Golden Hind, a luxury production which became known as "The Golden Behind", due to Spare's fleshy taste in female nudes. Too luxurious for its own good, it folded in 1924. By now things were starting to slip for Spare, and around this period he underwent a personal crisis which gave rise to The Anathema of Zos, a Nietzschean rant against conventional society which he published in 1927. Unlike the people in the polished artistic and literary milieux that he had temporarily moved in, Spare - artist, magician, and geezer - remained essentially working class. This probably contributed to his downfall, along with his disdain for Modernism and changing artistic fashions. Whatever the reasons, as his career stalled in the 1920s he fell back south of the river and stayed there for the rest of his life, living - in his own words - as "a swine with swine."

Spare was out of the limelight, but his real life (forget his 'career' for a moment) had long had a shadow side. He had lived in South London before - his family had moved from Smithfield to Kennington when he was eight - and it was down there, as a child, that he had apparently been seduced in some way by an elderly witch named Mrs.Paterson. He fell, as the expression has it, under her spell. As Spare would tell it later, Mrs Paterson introduced him to fortune telling with cards, and she had the power to 'materialise' thought-forms to the point where another person could see them. She also had the power to lasciviously transform herself from an aged crone to a sexually alluring woman, although some of Spare's art shows that, as far as he was concerned, this was a fluid distinction anyway. Today the social services would be round to Kennington before you could say "Beezlebub", but Spare's destiny was sealed. He could have said, like Marlowe's Dr.Faustus, "'Tis magic, magic, that hath ravished me."

Like the 1960s, the turn of the century was a good time to be interested in magic. Amid the decadence of the fin-de-siecle, the 'Occult Revival' was in full swing. The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn had been founded in 1887, allegedly after the chance discovery of some manuscripts in Farringdon Road book market, and its members included W.B.Yeats, Aleister Crowley, Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen, Dion Fortune, and the children's writer E.Nesbit. Magic was in the air, permeating - for example - the work of Aubrey Beardsley. Spare was too young for the original Golden Dawn, but after its schismatic break up he joined Aleister Crowley' s new order, the Argenteum Astrum, in 1909. Spare and Crowley were at one time friends, and it is often speculated that there may have been a physical relationship between them. Be that as it may, Spare was too much of a maverick to stay in the A.A. for very long, and he flunked the course. Crowley's hide-bound comment speaks volumes about both of them: "artist: can't understand organisation." Spare rejected far more of Crowley's style of occultism than he adopted, and his own, far more free-form and psychically-oriented magical methods are crystallised in his 1913 The Book of Pleasure (Self Love): The Psychology of Ecstasy.

Like the 1960s, the turn of the century was a good time to be interested in magic. Amid the decadence of the fin-de-siecle, the 'Occult Revival' was in full swing. The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn had been founded in 1887, allegedly after the chance discovery of some manuscripts in Farringdon Road book market, and its members included W.B.Yeats, Aleister Crowley, Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen, Dion Fortune, and the children's writer E.Nesbit. Magic was in the air, permeating - for example - the work of Aubrey Beardsley. Spare was too young for the original Golden Dawn, but after its schismatic break up he joined Aleister Crowley' s new order, the Argenteum Astrum, in 1909. Spare and Crowley were at one time friends, and it is often speculated that there may have been a physical relationship between them. Be that as it may, Spare was too much of a maverick to stay in the A.A. for very long, and he flunked the course. Crowley's hide-bound comment speaks volumes about both of them: "artist: can't understand organisation." Spare rejected far more of Crowley's style of occultism than he adopted, and his own, far more free-form and psychically-oriented magical methods are crystallised in his 1913 The Book of Pleasure (Self Love): The Psychology of Ecstasy.

Let's fast forward a few years to look at some of Spare's magic in practice, and to consider the beginnings of the Spare legend in his own lifetime: some of the tales that circulate about Spare make the London Borough of Lambeth seem like HP.Lovecraft's Arkham County. Three examples will be enough. The first takes place around the end of the Second World War, and is told by the late Francis X. King. A friend of King's - "then an art student, now a Chartered Accountant" - had met Spare, and the two of them had got on well. They both hated the fashions of modern art, which had become something of an obsessive topic with Spare. On the other hand, they disagreed strongly over magic, which King's friend scoffed at. When Spare mentioned that he was sometimes possessed by the spirit of William Blake, the friend countered with a stream of sympathetic psycho-babble about schizoid personalities, dissociated complexes, and the rest. This narked Spare into showing his hand: he completely believed in magic, he said, and he had actually been doing it all his life. More than that, he would give the friend a real demonstration of it next time they met.

Spare was living in a dank and mouldering basement in Brixton, and it was here the art student had his appointment with magic. It was grim in Spare's basement. It didn't smell too good, and it could be noisy, with waste pipes gurgling in the ceiling and buses driving past at street level. The friend wasn't feeling quite as phlegmatic as he had the week before. He had done a little reading in the meantime and it had made him nervous, as reading will. Nevertheless, King says, he felt his "firm adherence to the linguistic philosophy of A.J.Ayer would save him from being gobbled up by the demon Asmodeus or, indeed, any other unpleasantness".

On entering the dread basement, the first thing the friend noticed was a marked absence of cloaks, incense, magic pentagrams, and general Dennis Wheatley paraphernalia. Spare was eating a piece of pie, and when he had finished it, the demonstration could begin. In place of the usual mystic bric-a-brac were some drawings and papers covered with letters and graphic symbols. Spare announced that he was going to attempt an "apportation", i.e. the production of a material object from thin air. Somewhat dated now, apports were very much part of the lore of spiritualism, and were quite widely performed in the nineteenth century. Spare was going to produce living, freshly cut roses out of the atmosphere. Working in silence, he waved a drawing in the air for a minute or two before putting it back on the table. Spare was clearly concentrating very hard, and the strain was visibly showing in his face as he finally pronounced the word "Roses". There was a moment of tense, pregnant silence before the pipe in the ceiling burst, bringing down a deluge of sewage and old bathwater on their heads.

Like a lot of Spare stories, this neat tale has the air of being slightly too good to be true. But it is interesting that it seems to originate from the second party, the witness, and not from Spare himself (we'll see why later). King was a notably sane and scholarly writer, and his friend's narrative does have a ring of circumstantial truth about it. Of course, the whole thing lies entirely within the realm of coincidence, but this is not the case with the second story. Something else is going on there, both in the tale and the telling, which has been atmospherically done by Kenneth Grant - a senior British occultist and a key writer in the creation of the Spare legend.

Like a lot of Spare stories, this neat tale has the air of being slightly too good to be true. But it is interesting that it seems to originate from the second party, the witness, and not from Spare himself (we'll see why later). King was a notably sane and scholarly writer, and his friend's narrative does have a ring of circumstantial truth about it. Of course, the whole thing lies entirely within the realm of coincidence, but this is not the case with the second story. Something else is going on there, both in the tale and the telling, which has been atmospherically done by Kenneth Grant - a senior British occultist and a key writer in the creation of the Spare legend.

Spare was occasionally bothered by dilettantes and thrill seekers of one kind or another, and on one occasion two dabblers asked him to evoke an "elemental" to visible appearance. A couple of ectoplasm junkies looking for stronger kicks, they had seen the spirits of the human dead materialised at seances, but now they were on a psychic safari after rarer game. They wanted to see a non-human spirit. Spare tried to dissuade them, explaining that these entities embody atavistic forces from deep in the unconscious, and that it is better not to bring them up to the surface. But the dabblers insisted.

Spare drew a graphic symbol of his own devising on a piece of paper, and pressed it to his forehead. Nothing happened for a while. Then the poor light seemed to thicken and grow misty. A greenish mist now definitely seemed to be in the room, congealing into flitting, seaweed-like fingers and beginning to constitute "a definite, organised shape" with a nightmarish quality of absolute evil; "it entered into their midst, gaining more solidity with each successive moment. The atmosphere grew miasmic with its presence and an overpowering stench accompanied it; and in the massive cloud of horror that enveloped them, two pinpoints of fire glowed like eyes, blinking in an idiot face which suddenly seemed to fill all space." The dabblers panicked and begged Spare to send it away again, which he managed to do, but they were badly shaken by the experience. One of them was dead within a few weeks; the other was in a psychiatric hospital.

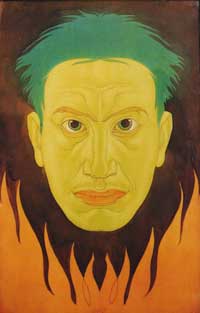

Kenneth Grant (painted, left, by Spare in 1950) has been underestimated as an imaginative writer in his own right, as well as a receptive ear for Spare's stories. This tale comes - presumably - from Spare, generically influenced by Grant's own avid reading of early 2Oth century visionary writers such as Machen and Lovecraft, and the pulp fictions of Sax Rohmer - the latter being no slouch with the miasmic green mist himself. People can certainly frighten themselves, even to death, but published corroboration is hard to find for this episode. If anything sets up even the slightest thee-dimensional co-ordinate here, it could be a comment that Spare made to his friend Frank Letchford. Letchford was not very interested in the occult, and Spare tended to play down his engagement with it when he talked to him. Spare told Letchford, late in life, that he was disenchanted with occultism, and that he'd had a friend who dabbled and became insane - which may be an unforced, untheatrical echo of some incident behind this story.

The third story, published several times with minor variations, is the most complex, relying on the imaginative collusion of a number of actors in the drama. It takes place in 1955, in the Islington house of an alchemist. Magical feuding had broken out between two occult groups, one headed by Kenneth Grant and the other by Gerald Gardner, the witchcraft revivalist. Gardner believed that Grant had "poached" a talented medium of his, an unstable young woman called Clanda, and he went to Spare for a talisman "to restore stolen property." Spare had no idea that this was to be used, in effect, against his friend Grant. The talisman Spare drew was apparently "a sort of amphibious owl with the wings of a bat and the talons of an eagle." It is interesting to note that Spare had a reputation among other occultists as somebody who could actually "do the business". Conversely, it seems Gardner recognised he had no ability himself, although he was an expert, which introduces an unexpectedly objective note into his own witchcraft.

At the magical meeting in Islington, Clanda lay upon an altar waiting to incarnate the goddess Black Isis, but instead things went badly wrong. She felt the temperature drop and imagined a great bird had crashed into the room, taking her up out of it and away. She saw the snow-covered roofs below, as in a flying dream, until the bird began to lose height over a wharf-like structure. She struggled in terror, and suddenly found herself back on the altar. Nobody is suggesting that Clanda went anywhere physically: it all took place, as they say, "astrally". Grant adds that a slimy, saline substance was left on the windowsill afterwards, seeming to pullulate slightly.

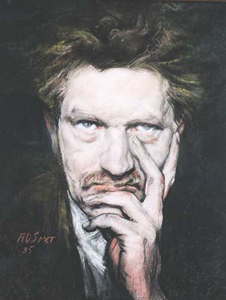

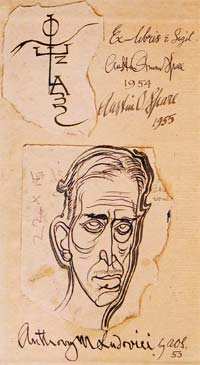

Enough of pullulating slime and back to Spare's art. At best it is exceptionally powerful, but one of the most peculiar things about it is his chameleonic range of styles. Spare's distinct modes - some at different periods, others contemporary with each other - have been compared to Beardsley, Michelangelo, Durer, and Blake, among others, but they have an intensity that goes beyond pastiche, with something unmistakably "Spare" about all of them. There are also his straight pastel portraits of ordinary South Londoners (which are among his best work), occult and automatistic graphics, and anamorphic distortions of perspective in a technique that Spare termed "siderealism". And then there are the strange graphics that Spare drew to "visualise sensation" in The Book of Pleasure, which are unlike anything that anybody else was doing at the time.

Enough of pullulating slime and back to Spare's art. At best it is exceptionally powerful, but one of the most peculiar things about it is his chameleonic range of styles. Spare's distinct modes - some at different periods, others contemporary with each other - have been compared to Beardsley, Michelangelo, Durer, and Blake, among others, but they have an intensity that goes beyond pastiche, with something unmistakably "Spare" about all of them. There are also his straight pastel portraits of ordinary South Londoners (which are among his best work), occult and automatistic graphics, and anamorphic distortions of perspective in a technique that Spare termed "siderealism". And then there are the strange graphics that Spare drew to "visualise sensation" in The Book of Pleasure, which are unlike anything that anybody else was doing at the time.

Not so long ago, people would have said the greatest artist of the twentieth century was Picasso, but now they would probably name Marcel Duchamp. Picasso was formidably fertile within art, but Duchamp made the quantum leap of playing with the idea of 'art' itself, not just doing things within it. There is a similar distinction to be made between Crowley and Spare. Spare was less interested in magical beliefs than in the nature of belief itself - he was interested in 'how' to believe, and not 'what' to believe. He saw belief as something free-floating, which could be channelled and re-directed to different objects (like Freud's idea of "libido", which often sounds like something out of hydraulic engineering). Spare, in other words, conjured with belief. And that is probably all that needs to be said about his magic here, although its components - the "Zos and the Kia"; "the death posture"; "sigils" and "the alphabet of desire", "atavism" and the rest - are increasingly bruited around in occult writing. The most intelligent and interesting summary of Spare's sorcery is to be found in Gavin W. Semple' s already rare and sought-after 1995 book Zos-Kia (out of print and not in the British Library), from which I have lifted the distinction about the 'how' versus 'what' of belief.

There is a third strand to Spare's career, inseparable from his art and magic. Like Salvador Dali and Baron Corvo, Spare was one of the great confabulators: a lie, he used to say, was just a truth in the wrong place. He could never stay with the daylight facts for long. In 1936, for example, Adolf Hitler tried to commission a portrait from Spare and offered to fly him out to Germany to paint it, but Spare defiantly refused, and briefly became a hero in the newspapers. So far, so true. But a couple of years later Spare revived the story and made the papers again. This time he had flown to Germany, he had made a portrait of Hitler, and he was going to incorporate it into an anti-Nazi work, perhaps even a magical one.

And this is only one of Spare's many interesting experiences. He studied hieroglyphics at first hand in Egypt; he had a respectful letter from Freud, deferring to his greater genius; he was the only survivor of a torpedoed troopship; he spent all night in No-Man's Land in a pile of corpses (in fact he didn't get to France until WWI had finished, although he did get as far as Blackpool) - and so it goes on. Even the existence of Mrs. Paterson is enigmatic, although an old woman of that name did live nearby.

Among the books that Kenneth Grant pressed on Spare was one by Hans Vaihinger, The Philosophy of 'As If'. Vaihinger (1852-1933) was a Kantian philosopher, remembered for his "fictionalism" (the 'As If' principle). He suggests that human thought proceeds by the use of unreal fictions, since the truth - following Kant's idea of the unknowable noumenon, and Schopenhauer's pessimism about how much we can really know - is impossible to reach. Instead, for Vaihinger, ideas like God, freedom, human rights, Black Isis and so on would be "beautiful, suggestive and useful fictions", but fictions none the less (this is slightly different from full-blown pragmatism, which is only concerned with usefulness and wouldn't even bother with the concept of falsity). Spare devoured all this with fascination, and the 'As If' principle consolidated a pivotal part of his magical thinking. In Spare's hands, it is one of the furthest points in the tradition of romantic epistemology, and he took it into regions where Vaihinger might well have feared to tread. It is virtually a definition of his magic: in Grant's paraphrase, "By Belief in a concept, either true or false (objectively speaking) wonders may be wrought and reality realized in the flesh."

Certainly Austin Spare was touched by that whole range of phenomena we conveniently shorthand as 'genius', but his greatest work may well have been himself.